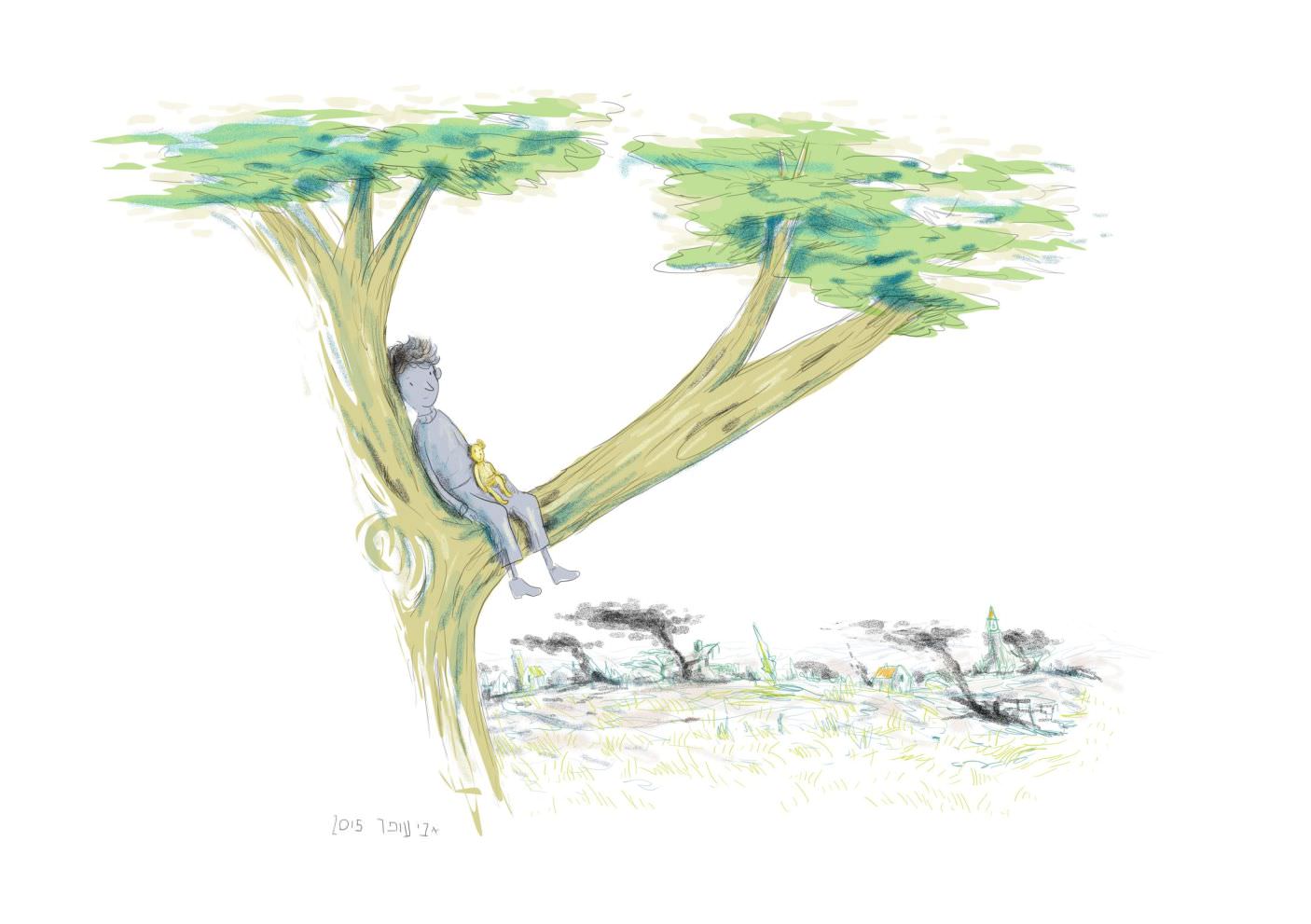

An illustration from Iris Argaman’s book “Bear and Fred,” with “heartrending” illustrations by Avi Ofer. Credit Avi Ofer/Hakibbutz Hameuchad

A teddy bear accompanied Fred Lessing in his wanderings from one hiding place to another during World War II and became a symbol after being loaned to Yad Vashem. Now the subject of a children’s book, Lessing reveals how he was persuaded to let someone else tell his story.

Fred’s teddy bear is not the most impressive in the world; it’s not even the most impressive in Jerusalem. Its fur is tattered, its gray head sporting eyes stitched together with red thread. It’s skinny, faded, dirty and nameless — and yet it became Yad Vashem’s “Mona Lisa.”

This little toy has symbolized the memory of the Holocaust for millions of children who survived, commemorating the million and a half who perished.

The teddy bear belongs to a Dutch survivor, Alfred (“Fred”) Lessing, who moved between hiding places during World War II. He later moved to the United States, with his teddy bear accompanying him wherever he went. In 1996, the teddy bear reached Israel alone and was showcased at Yad Vashem as part of an exhibition called “No Child’s Play,” which was on display for 17 years.

Curator Yehudit Inbar once said that when the teddy bear arrived in Israel and was taken out of a gigantic box, it looked like a fetus. She burst into tears upon seeing it, and when she told the dispatcher about the teddy bear’s history, he started crying too. Since it was put on display, many tearful world leaders have been photographed next to it.

The story of this emotional journey opens “Hadoobi shel Fred” (“Fred’s Teddy Bear,” but “Bear and Fred” in English), a new book by Iris Argaman. This children’s story about the Holocaust is told from the perspective of a teddy bear. It was published earlier this year by Hakibbutz Hameuchad, with heartrending illustrations by Avi Ofer.

Fred Lessing’s teddy bear on display in the “Children in the Holocaust: Stars Without a Heaven” exhibition at Yad Vashem. Credit: Courtesy of Fred Lessing/Yad Vashem

Last June, it won Yad Vashem’s prize for a children’s or young adult’s book on the topic of the Holocaust. This prize was established by the late Sandra Brand in memory of her only child, Bruno, who perished in the Holocaust. The book is now being translated into Italian.

Argaman has aimed the book at children aged 6-8. She describes it as “a story of a friendship between a boy and his brave teddy bear, in the shadow of a terrible war.” She hopes it won’t be read only before Holocaust Remembrance Day. She enjoyed a long correspondence with Lessing and after he agreed to let her write the book, decided to visit the teddy bear in Jerusalem.

She describes that meeting in the book’s epilogue: “On a rainy winter day, I went to Jerusalem, to Yad Vashem, in order to meet the bear. Dark clouds filled the sky and heavy rain fell. I reached the hall in which it was on display, wet and shivering with cold. The meeting was very moving for me. I stood in front of the little teddy bear, who stood alone in a glass case, and I couldn’t move. I whispered words only he could hear. I gave him regards from Fred, and told him I’d write his story so other children would get to know him and realize how charming and special he was.”

Holocaust lecturer

The teddy bear probably has a lot to say on the subject. But since it’s an inert object, Argaman connected me instead to the story’s other hero, Fred Lessing. He’s an 80-year-old Holocaust survivor, married with four children and seven grandchildren, who lives in Birmingham, Michigan. In a Skype interview, he repeated the story of himself and his beloved teddy bear, in the manner he uses when talking to children in lectures about the Holocaust that he’s been giving for decades.

“In 1940 the Germans invaded Holland. I was 4 years old and don’t remember much about those days. My mother, father and three brothers lived in Delft, a beautiful city near The Hague. When I was 6, on October 23, 1942, our family was on a list of Jews who were to be transported for “resettlement in the East,” which in retrospect meant death camps. My parents decided to go into hiding instead of getting on that train.

“It was an ordinary day, I played with my brother upstairs, a technician was repairing a stove in the kitchen and our mother called us. From her voice we could tell it was something important, frightening and serious. She hugged us and said ‘you are Jewish children but if anyone hears that they’ll kill you.’ This was the first time in my life that I heard I was Jewish. She asked us to pretend we were just going out, not taking anything with us, and told the technician we’d be back soon. We never returned home.

An illustration from Iris Argaman’s book “Bear and Fred,” with “heartrending” illustrations by Avi Ofer. Credit: Avi Ofer/Hakibbutz Hameuchad

“I didn’t listen to her and took my little teddy bear with me. It was the only thing I took and the only thing I had for the next three years beside the clothes on my back. The teddy bear survived the war years with me.”

In the book the teddy bear’s head flaps around until it’s better attached. What really happened?

“He was already missing a head when I first took him into hiding after a dog pounced on him and tore it off. I was with many Christian families while I hid, going from one to the other. My parents changed my name and dyed my hair, they obtained forged documents for us and we pretended to be Christians. For the first two and a half years I was alone with numerous families. That was a very difficult period for me. While I was hiding with a family in Amsterdam I suffered from diphtheria, my mother came to visit and sewed a new head for the teddy bear.”

Lessing, who retired last year, was a psychotherapist and lecturer in philosophy, “but much of my identity is one of a Jewish Holocaust survivor. I’m a total atheist and grew up in a secular family with no signs of Jewish culture around me, but I was Jewish since Hitler said I was. For 40 years after the war no one talked about the Holocaust, and I grew up as a regular American kid. Toward the end of the 1980s, children who had been in hiding started coming out and telling their stories, giving interviews and meeting each other.

An illustration from “Bear and Fred.” Credit: Avi Ofer/Hakibbutz Hameuchad

“The first such meeting took place in 1991, in New York. My wife and I were supposed to board a plane for New York. We were on our way out of the house when she asked if I’d taken everything. I then said — wait a minute! I felt like I had to take my little teddy bear with me. It was like in 1942 when I grabbed it just before leaving the house. It drew a lot of attention by other former children at the meeting. Even though none of us were still children, they all identified with my teddy bear. Since then it has joined me everywhere I’ve been invited to speak.

“Although many years have passed and I’m an adult who knows exactly what happened in the Holocaust, when I tell my story I have to remember that I was only a child then, which is why I took my teddy bear with me. I agreed to lend it to Yad Vashem after I was told the exhibition would last only a few months. I didn’t want to part from him, but Bear and I decided he should go. When he reached Israel, a new chapter began in his life. Since the exhibition continued for many years, my brother Ed bought me a stand-in bear.”

Harsh realities

Lessing stops and goes to a baby’s high chair, from which he pulls out a fat and woolly teddy bear, the stand-in one. I exit the room and return with a sad Japanese teddy bear I had bought my daughter after reading the book. I couldn’t help it.

Is it important for you that every child has a teddy bear to help it contend with harsh realities?

“It doesn’t have to be a teddy bear. My daughter had a blanket she called Mynie, which served the same purpose my teddy bear did for me. An object from one’s past is very important for children. This is the first object one chooses to connect with. My teddy bear couldn’t talk but it had a truth and meaning that nothing else had. When I hid among different families my teddy bear reminded me of my mother and family and it was important as a symbol. It also constituted a way of expressing love and consolation. After the war it reminded me of my childhood during the Holocaust, making it a very important object. Many parents throw out such objects since they are dirty, but I suggest that they shouldn’t. These are very precious items for children.”

Iris Argaman told me that it wasn’t easy for you to agree to her writing this book.

Fred Lessing visiting Bear during the “No Child’s Play” exhibition at Yad Vashem in 1997. Credit: Yad Vashem

“I deliberated for a long time over that issue. I was warned by other survivors not to let anyone else write my story or illustrate it, since you never know what they might do to it. Ultimately I wrote Iris a long letter, telling her I couldn’t be part of it since I was the only one who could accurately relate my story — it’s important to me that testimonies aren’t exaggerated or stray from things as they happened. After sending the email I went to bed.

“The next morning I changed my mind. I wrote her again, saying that on the previous day I’d written as a survivor but that day I was writing as a teacher. I believe in education and in the importance of children learning about the Holocaust, and that if I’m not writing a children’s book about the Holocaust I’ll support her. Iris was glad and her illustrator did an amazing job. When I saw the cover I realized that he understood that teddy bear, with an illustration showing me looking after it and it looking after me. It’s so deep. The book is wonderful and moving. My son cried when he read it.”

Is it important to explain the Holocaust to children?

“That’s a question that comes up all the time. Eighty percent of Holland’s Jewish population didn’t survive. All my classmates were murdered. A million and a half Jewish children perished. Obviously you don’t show small children history books. The prevailing wisdom here is that you don’t expose children under 13 to it. In conversations I have with children I always try to avoid the scary aspects of the Holocaust and tell my story in a very personal way, adapted to the audience.”

In one of the book’s pages Iris writes in the teddy bear’s name: “Every night Fred would whisper that he misses his father, mother and brothers, that he’s sad to be alone, that the world is scary and that he’s lucky that I’m his best friend. Fred whispered those things, and while talking to me he stroked his face with my paw. Sometimes Fred shed small and warm tears and I wiped them away.”

Who is the target audience for such a sad book?

“Iris’s book is suitable for any age because of the teddy bear. It doesn’t mention the word Holocaust. At the end of the book the war is over and only then do you find out there was one. I’m surprised by your calling it sad, it has a happy ending. It’s one of the happy stories about an entire family that survived the Holocaust.”

The temporary exhibition has closed since that time. A new exhibition called “Children in the Holocaust: Stars Without a Heaven” shows selected items from the world’s largest collection of children’s games from that period. It opened last winter at Yad Vashem. Lessing says that “the teddy bear is shown in this exhibition as well, but I’m not happy with it since it’s included in a showcase with many other toys. He’s so small that it’s hard to find him — the other toys are so large and clean, as if they were new. A year has passed and I have to decide what to do with him. I don’t have a problem if he’s there in his own display box, but if he’s with many others I want him back. They called him Yad Vashem’s ‘Mona Lisa’! I’m still alive and I’ll take him to talks I give.”

Originally Published HERE