March of the Living Survivor Database

Since 1988, approximately 300 Holocaust Survivors have traveled to Poland and Israel with the International March of the Living.

Below is a list of our cherished March of the Living survivors, their hometowns, and the delegations with which they have traveled.

This list contains the names of survivors provided to us by local delegations to the International March of the Living office. We apologize for any inadvertent omissions. Please email us with any names of survivors that might be missing, and any other corrections.

ANGELA OROSZ-RICHT

Auschwitz, HUNGARY - Canada

1944 -

Delegation: Coast to Coast

Camps: Auschwitz

FRITZIE WEISS FRITZSHALL

Klucarky, Czechoslovakia - USA

1929 -

Delegation: NY/NJ

AGNES KAPOSI MBE

Debrecen, Hungary - United Kingdom

1932 -

Delegation: United Kingdom

ERNST VERDUIN, Z"L

Amsterdam, Holland - Holland

1925 -

Delegation: United Kingdom

Camps: Auschwitz-Birkenau

DORA ROTH AKERMAN, Z"L

Rosvegovo, Czechoslovakia - USA

1927 - 2020

Delegation: Western USA

MALA TRIBICH MBE

Piotrków Trybunalski, Poland - United Kingdom

1930 -

Delegation: United Kingdom

ZIGI SHIPPER BEM, Z"L

Lodz, Poland - United Kingdom

1930 - 2023

Delegation: United Kingdom

NOAH KLIEGER, Z"L

Strasbourg, France - Israel

1926 - 2018

Delegation: International

GIDEON LEVIN

Sudetenland, Czechoslovakia - Israel

1935 -

Delegation: International

NANCY KLEINBERG, Z"L

Wierzbnick, Poland - Canada

1927 - 2022

Delegation: Toronto

SIDONIA LAX, Z"L

Przemysl, Poland - USA

1927 - 2022

Delegation: LA

Camps: Auschwitz

IRENE MERMELSTEIN, Z"L

Irshava, Czechoslovakia - USA

1929 - 2022

Delegation: Miami

ELLY GROSS, Z"L

Șimleu Silvaniei, Romania - USA

1929 - 2022

Delegation: NY/NJ

Camps: Auschwitz-Birkenau, Cehei Ghetto

ERNEST BLOCH, Z"L

Nyrsko, Czechoslovakia - Canada

1927 - 2012

Delegation: Toronto

Halina Birnbaum

Warsaw, Poland - Israel

1929 -

Delegation: Israel

Camps: Warsaw Ghetto, Majdanek, Auschwitz

JANOS FORGACS, Z"L

Godollo, Hungary - Hungary

1928 - 2022

Delegation: Hungary

Camps: Auschwitz

DORA JABKO, Z"L

Lodz, Poland - USA

1929 - 2015

Delegation: Broward

Camps: Ravensbruk. Lodz Ghetto

FREDDIE KNOLLER BEM, Z"L

Vienna, Austria - United Kingdom

1921 - 2022

Delegation: United Kingdom

ETA MANDELBERGER

Lodz, Poland - USA

1922 -

Delegation: Broward

Camps: Auschwitz, Bergen Belson

BERNARD GROSS, Z"L

Palatka, Czechoslovakia - USA

1926 - 2020

Delegation: Broward

GEORGE HERCZEG, Z"L

Nagyvisnyó, Hungary - Canada

1925 - 2010

Delegation: Toronto

ROMAN ZIEGLER, Z"L

Dabrowa Górnicza, Poland - Canada

1927 - 2020

Delegation: Toronto

RENEE SALT BEM

Zdunska-Vola, Poland - United Kingdom

1929 -

Delegation: United Kingdom

Hershel Greenblat

Grisha Grinblat, Ukraine - USA

1941 -

Delegation: Southern USA

HARRY (CHAIM) OLMER BEM

Sosnowiec, Poland - United Kingdom

1927 -

Delegation: United Kingdom

IRENE ZISBLATT

Polena, Hungary - USA

1928 -

Delegation: Broward

Camps: Auschwitz/Birkenau

HEDY BOHM

Oradea, Romania - Canada

1928 -

Delegation: Toronto

Camps: Oradea ghetto, Auschwitz-Birkenau

Tzvi Klein

Somotor, Czechoslovakia - Israel

1931 -

Delegation: Israel

Camps: Auschwitz-Birkenau

ALFRED GARWOOD

Krakow, Poland - United Kingdom

1942 -

Delegation: United Kingdom

BARBARA MARIA FRANKISS

Warsaw, Poland - United Kingdom

1938 -

Delegation: United Kingdom

EUGENE LEIBOVITZ, Z"L

Uzhorod, Czechoslovakia - USA

1928 - 2022

Delegation: Miami

PAUL FRYBERG OBM, Z"L

Lodz, Poland - Australia

1925 - 2019

Delegation: Australia

SABINA MILLER BEM, Z"L

Warsaw, Poland - United Kingdom

1922 - 2018

Delegation: United Kingdom

DAVID BORGENICHT, Z"L

Krynica, Poland - Poland

-

Delegation: Broward

Camps: Prokocim, Biezanow, Skarzysko, Buchenwald, Theresienstadt

AVIVA PTACK

Poland - Canada

1941 -

Delegation: Montreal

Camps: DP camps in Germany

Eva Kuper

Bielany , Poland - Canada

1939 -

Delegation: Montreal

Camps: Warsaw Ghetto, Umschlagplatz

Martin Stern

Netherlands, Netherlands

1938 -

Delegation: UK

Camps: Westerbork, Theresienstadt

JAKOB “KUBA” ENOCH, Z"L

Krakow, Poland - Australia

1926 - 2021

Delegation: Australia

Endre (Andy) Sarkany

Budapest, Hungary - USA

1936 -

Delegation: Voices of Hope

Camps: Budapest Ghetto, Mauthausen

TUWIA (TUVIA) LIPSON, Z"L

Lodz, Poland - Australia

1925 - 2020

Delegation: Australia

MARTIN BARANEK, Z"L

Starachowice, Poland - USA

1930 - 2023

Delegation(s): Miami, Toronto

ISAAC GOLDSTEIN, Z"L

Bialystok, Poland - USA

1925 - 2018

Delegation: Western USA

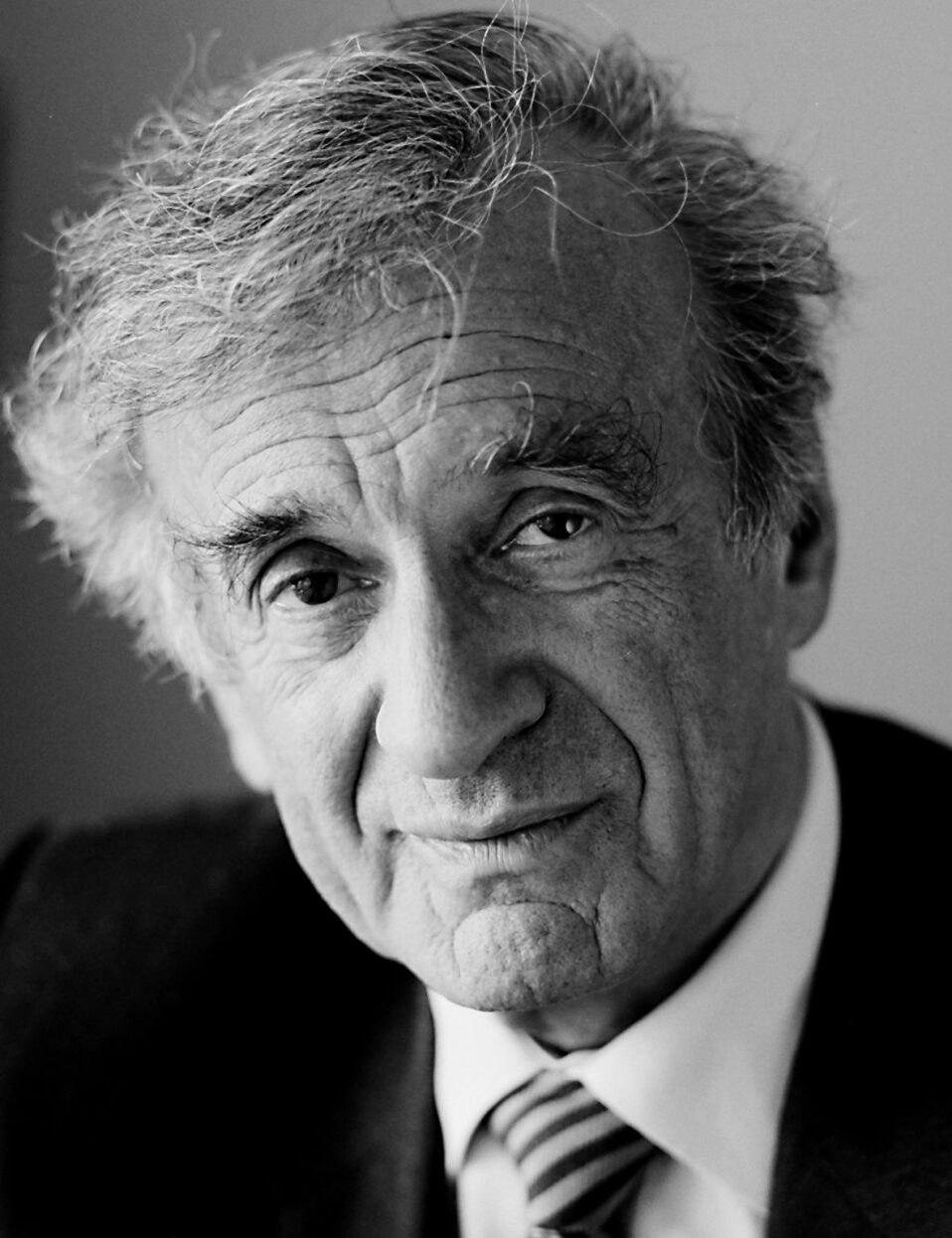

ELIE WIESEL, Z"L

Sighetu Marmației, Romania - USA

1928 - 2016

Delegation: International

TED BOLGAR

Sarospatak, Hungary - Canada

1924 -

Delegation: Montreal

Camps: Satoraljaujhely, Auschwitz-Birkenau

Luis Opatowski Goldberg

Brussels, Belgium - Mexico

-

Delegation: Mexico

Camps: Stutthof Labor Camp

STEPHANIE HELLER, Z"L

Prague, Czech Republic - Australia

1924 - 2019

Delegation: Australia

ARIE SHILANSKY

BIRTH CITY, United Kingdom - Israel

1929 -

Delegation: United Kingdom

Arieh Pinsker

Transylvania, Romania - Israel

1930 -

Delegation: Israel

Camps: Birkenau

RABBI ISRAEL MEIR LAU

Piotrków Trybunalski, Poland - Israel

1937 -

Delegation: International

SAM LASKIER, Z"L

Warsaw, Poland - United Kingdom

1927 - 2020

Delegation: United Kingdom

ABE NEWERSTEIN, Z"L

Warsaw, Poland - USA

1924 - 2006

Delegation: Broward

Camps: Warsaw Ghetto, Umschlagplatz

AREK HERSH MBE

Siaradz, Poland - United Kingdom

1928 -

Delegation: United Kingdom

Camps: Otoschno, Chelmno Ghetto, Lodz Ghetto, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Theresienstadt

EFRAIM SZTROCHLIC, Z"L

Chelach, Poland - Australia

1925 - 2020

Delegation: Australia

WILLIAM (BILL) KUGELMAN, Z"L

Sosniwice, Poland - USA

1924 - 2023

Delegation: Western USA

EVE KUGLER BEM

Halle, Germany - United Kingdom

1930 -

Delegation: United Kingdom

GYORGI NEMES

Budapest, Hungary - Canada

-

Delegation: Montreal

Camps: Ravensbrook, Mauthausen

VESNA DOMANY HARDY

Zagreb, Croatia - United Kingdom

-

Delegation: United Kingdom

HARRY BAIKOWITZ

Kaunas, Lithuania - Canada

-

Delegation: Montreal

Camps: Feldafing