On the 70th anniversary of the world’s most famous trial, the prosecutors’ wise approach still offers a lesson for us.

SS Major General Jürgen Stroop (center) watches housing blocks burn during the suppression of the Warsaw ghetto uprising. This photo was part of the Stroop album submitted into evidence at the Nuremberg trial. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration, College Park

By Edna Friedberg

arguably the most famous trial in history, recognizable by the name of the city alone. From its start 70 years ago today, media coverage of the trial was unprecedented. During hurried renovations at Nuremberg’s Palace of Justice, workers added both a visitors’ gallery and a press gallery. Also crucial was the installation of equipment and wiring for a system of simultaneous translation, exponentially expanding the audience for the trial. More than 400 visitors observed the proceedings every day for a year, in addition to 325 newspaper, radio, and newsreel correspondents from 23 different countries. These reporters gave millions of people a seat in the courtroom.

But what were they watching? Were the proceedings dramatic? Rebecca West, the acclaimed British writer, covered Nuremberg for the New Yorker. In August 1946, as the case entered its 10th month, she wrote, “[T]he courtroom is a citadel of boredom. Every person attending it is in the grip of extreme tedium.” How could a trial for some of the most ghastly and massive crimes ever committed—crimes that continue to horrify and fascinate us—be dull? The answer lies in a most deliberate prosecutorial strategy, one to which we all owe a debt of gratitude today.

Keenly aware of the world’s gaze, the creators of this innovative international court deliberately assembled a public record of the staggering crimes committed by Germans during World War II, including those during the Holocaust. Nineteen investigative teams scoured records, interviewed witnesses, and visited the sites of atrocities to build the case. American chief prosecutor Robert H. Jackson (also a U.S. Supreme Court justice) worried that “unless record was made … future generations would not believe how horrible the truth was.”

Jackson’s team shared his concern. As another American prosecutor, Robert Storey, later wrote, “The purpose of the Nuremberg trial was not merely, or even principally, to convict the leaders of Nazi Germany … Of far greater importance, it seemed to me from the outset, was the making of a record of the Hitler regime which would withstand the test of history.” Indeed, evidence offered at Nuremberg laid the foundation for much of what we know about the Holocaust, including the details of industrial-scale murder at Auschwitz and the now iconic statistic of 6 million Jewish dead.

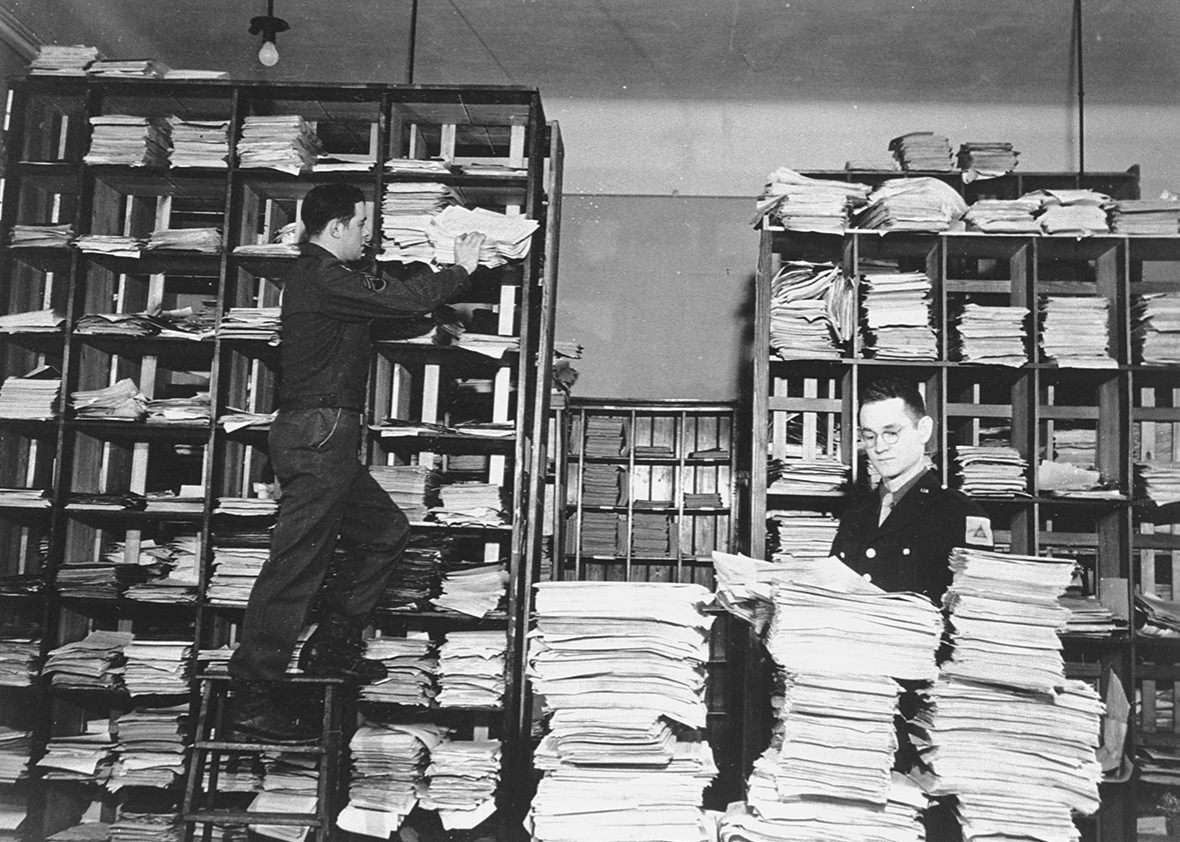

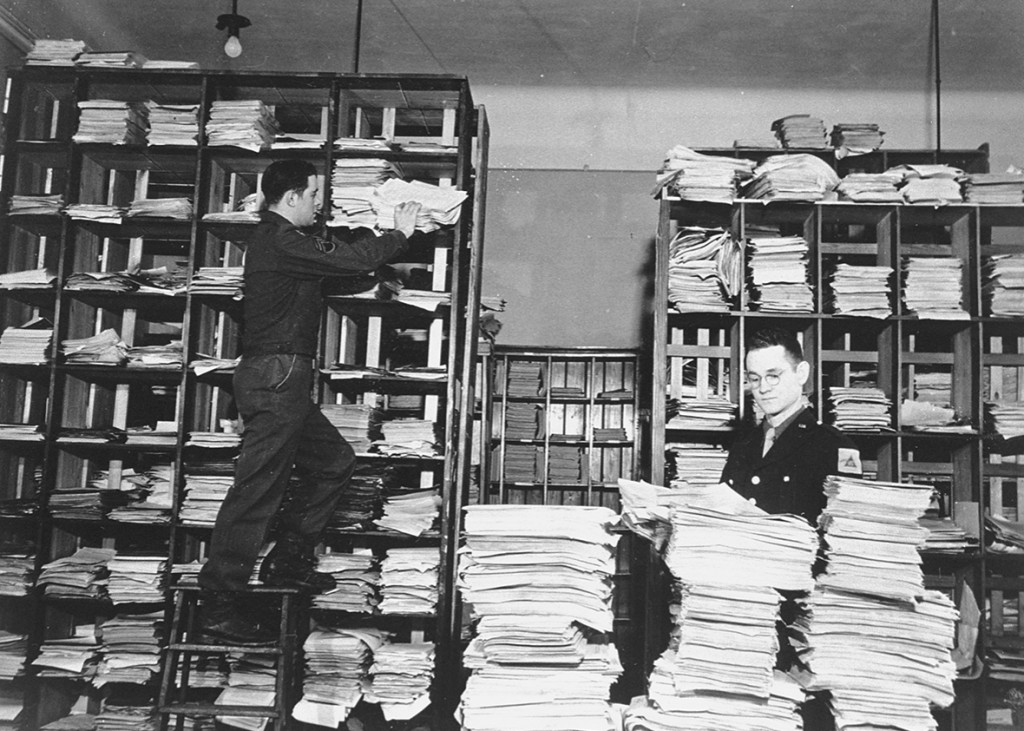

In order to avoid any accusation of reliance on potentially biased personal testimony, prosecutors decided to base their case primarily on documents written by the Germans themselves. Nazi officials had deliberately disposed of many papers near the war’s end, and other records were destroyed by bombing raids. Allied armies nevertheless captured millions of documents during their conquest of Germany in 1945. In total, Allied prosecutors submitted some 3,000 tons of records at Nuremberg.

The management of what was literally a sea of paper was a herculean task, especially when one remembers that the tribunal opened only a few months after the end of the war. Many of these documents have subsequently proved treasure troves for historians. The prosecutors’ approach did not offer daily drama—but it was no less momentous for its frequently dry presentation.

Even where central files were destroyed, the Allies were able to reconstruct some events from other sources. The Reich Security Main Office records, for example, were burned in the basement of its Prague regional headquarters, but copies were collected from local Gestapo offices across Germany. And both the Wannsee Conference Protocol (which documented the complicity of various state agencies), and the Einsatzgruppen Reports (which described mobile killing units that shot more than 1 million civilians) were among the documents submitted at Nuremberg during a series of trials. Each has proven critical to our understanding of the “Final Solution” today. They demonstrate the development of a genocidal strategy and suggest warning signs to watch for in crisis zones now.

The historical record established at Nuremberg was not based on paper alone. Nazi Germany’s dedicated filming of itself was turned into evidence of its crimes. From the earliest beginnings of the Nazi Party, photographers and camera crews recorded (often proudly) what they accomplished in pursuit of their ideology. As Allied troops advanced into German territory, teams of military personnel worked tirelessly to locate and catalog this photographic material.

As prosecutor Jackson declared in his opening statement, “We will show you their own films.” On Nov. 29, 1945, just one week into the trial, the prosecution showed an hourlong film titled “The Nazi Concentration Camps,” a montage of German footage. When the lights came up in the Palace of Justice, all assembled sat in silence. The human impact of this visual evidence was a turning point in the trial. It brought mass atrocities into the courtroom.

In addition to official images, individual German soldiers and police made numerous photographs and films. They recorded the public humiliation of Jews, as well as deportations and conditions in concentration camps. Allied prosecutors submitted into evidence a personal album of photographs taken on the orders of SS leader Jürgen Stroop to document the destruction of the Warsaw, Poland, ghetto uprising in spring 1943. According to Stroop’s own calculations, his forces captured more than 55,000 Jews and, of these, murdered at least 7,000 people and sent 7,000 more to the Treblinka killing center.

Taken together, the documents, photographs, and film presented at the Nuremberg tribunal and in its 12 subsequent trials continue to provide unimpeachable evidence of the massive crime we now call the Holocaust. Even before any verdicts were rendered, the court had provided a groundbreaking public service and antidote to future denial. As we consider court cases today, whether domestic or in international jurisdictions, we should remember the centrality and power of a public day of reckoning, for survivors and for societies.

Sometimes verdict and punishment are not the end of the story. Trials offer a way for communities—be they local or global—to reaffirm their values and openly declare their defense of them. The Nuremberg court was precedent-setting in many ways, establishing that “following orders” was not a legitimate defense for criminal acts and that heads of state could be subject to prosecution. But the historical documentation established in that courtroom is no less important a legacy. In her dispatch from the trial, Rebecca West referred to Nuremberg as “the historic peep show.” Yes, this trial was carefully staged—though not for lurid voyeurism but instead as a cautionary confrontation with state-sponsored criminality and an unimpeachable record of its evils.

Edna Friedberg is a historian at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Original article published HERE