Actor Rachel Weisz, left, and U.S. historian Deborah Lipstadt at the world premiere of “Denial,” at the Toronto International Film Festival, September 11, 2016. Credit: Fred Thornhill/Reuters

Rokhl Oyerbakh and Deborah Lipstadt disrupted the male-dominated study of the Shoah. The re-energized Holocaust denial on show this election season gives the two upcoming films about them a depressing relevance.

In April 1946, a memorial was held in Warsaw marking the third anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. The only woman to appear on the program that night was Rokhl Oyerbakh, one of only three surviving members of the Warsaw Ghetto’s Oyneg Shabes collective.

Directed by historian Emanuel Ringelblum, Oyneg Shabes created an underground archive of Polish Jewish life, the largest, most extensive of several archival projects active in the ghettos of WWII. They collected historical accounts of Warsaw Jewish life, pre- and post-war, as well as diaries, photographs, leaflets, and all manner of ephemera − even candy wrappers and tram tickets.

During her time in the Ghetto, Oyerbakh was a prolific member of the collective, while also acting as director of the Ghetto’s soup kitchen under the auspices of the Aleynhilf − the Ghetto self-help organization.

After decades of relative obscurity, the Oyneg Shabes story is being told in a new docu-feature to be released in 2017, “Who Will Write Our History”, based on Samuel Kassow’s monumental eponymous work.

‘I want to stay alive…to see the moment of revenge’

In the words of Kassow, “To write was to resist, if only to bring the killers to justice.” For Oyerbakh, personal survival was explicitly tied to the survival of the Oyneg Shabes archive.

During the great deportation to Treblinka in 1942, upon handing over part of the archive for burial (in the hope of protecting the collection from the Nazis), Oyerbakh wrote, “I want to stay alive. I am ready to kiss the boots of the worst scoundrel just to be able to see the moment of revenge. REVENGE REVENGE remember.”

Jewish prisoners being led out of the Warsaw Ghetto following the uprising in 1943. Credit: WWII War Crimes Records

While in the ghetto Oyerbakh escaped deportation and other close calls, finding a job in a factory in late 1942, then escaping to the Aryan side in early 1943. Having survived, she did not waste one minute in her quest for justice, through dogged research, writing and recording. At the end of 1945 she went to Treblinka to gather information on Nazi war crimes as a member of an official Polish fact finding group. When she moved to Israel in 1950 she joined Yad Vashem as the founder and director of the Department for the Collection of Witness Testimony. Her innovative approach to collecting eyewitness testimony would play a crucial role in the prosecution of Adolf Eichmann.

But at that April 1946 memorial evening in Warsaw, not everyone yet understood the role of witness testimony or the urgency of recovering the treasures buried by Ringelblum and his associates. Mendel Mann, an attendee recalled: “With a stubbornness that deeply affected me, [Oyerbakh] … cried out, ‘there is a national treasure under the ruins… We cannot rest until we dig up the archive… I will not rest, and I will not let you rest. We must rescue the Ringelblum Archive.’”

Oyerbakh implored the crowd to get to work on this sacred task, but as Mann recalled, she was met with a “cool reception.” Despite the indifference of the audience that night, the search for finally began in the summer of 1946 and the first Ringelblum cache was found soon after that.

Remembering the living as well as the dying

Almost exactly 50 years later, the historicity of the Holocaust would be on trial, quite literally. On September 5, 1996, the American historian Deborah Lipstadt was sued in a British court by pseudo-historian David Irving, accusing Lipstadt of libel for characterizing him as a Holocaust denier.

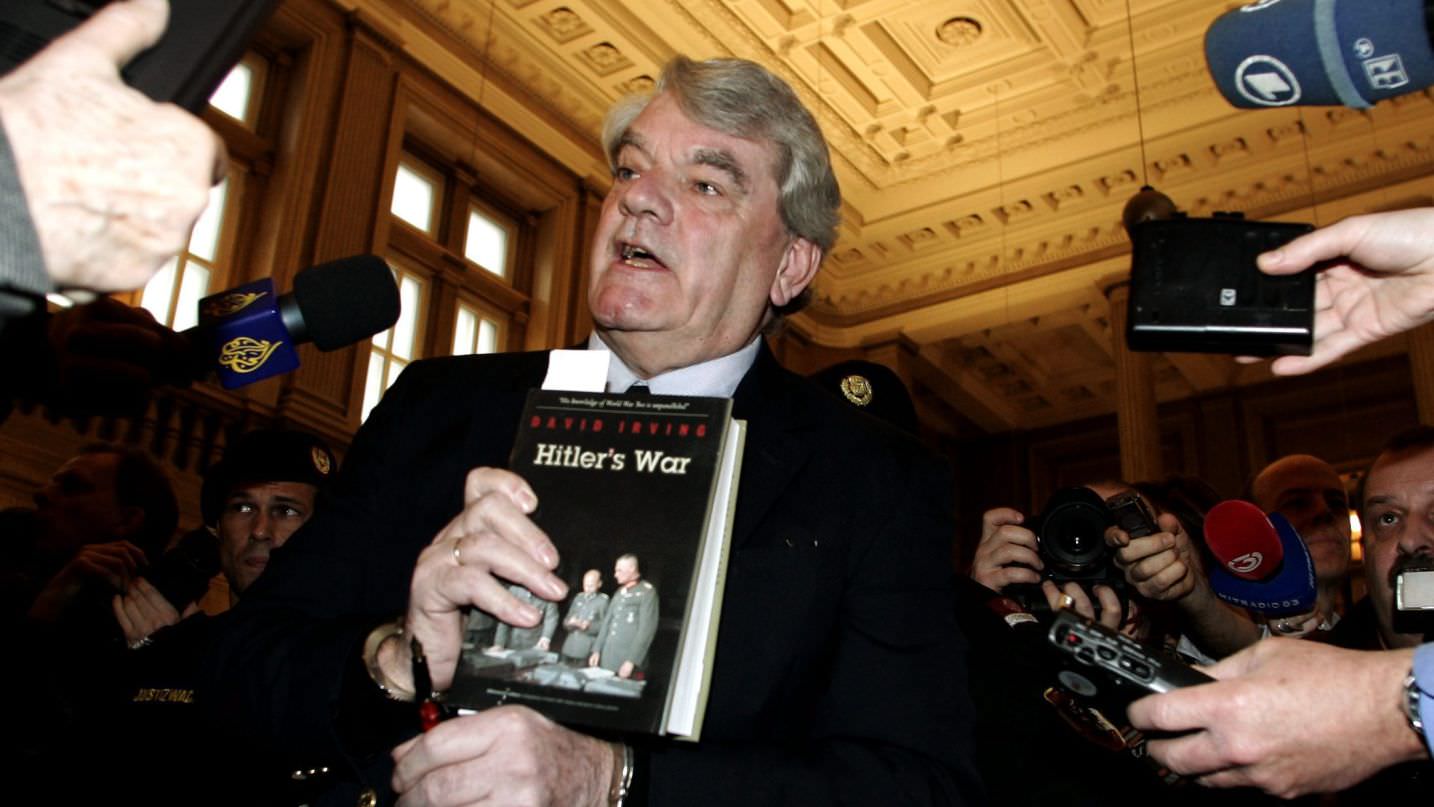

Right-wing British historian David Irving holds his book “Hitler’s War” when arriving at a court in Vienna, on Feb. 20, 2006. Credit: Hans Punz, AP

Oyerbakh and Lipstadt, one a writer and public intellectual of the inter-war, European mold, the other an American born and trained historian, both found themselves at historic turning points. By dint of circumstance, talent, and personal force of will, both rose to the task as guardians of memory, speaking, each in her own way, for the murdered.

The two historians also represent the two fronts of memory work left to post-war Jewry: one facing the outside world, refuting those who would deny the murder of European Jewry. The other front inward facing: shaping how Jews would understand what had been destroyed and how. For the Oyneg Shabes members, history was to be “an antidote to a memory of a catastrophe which, however well intentioned, would subsume what had been into what had been destroyed.”

Lipstadt’s battle with David Irving made front page news around the world while Oyerbakh’s story is little known outside those who study Polish Jewry or the history of the Holocaust. This fall Denial, a feature film based on Lipstadt’s battle with Irving will be released. Rachel Weisz plays Lipstadt, and character actor Timothy Spall playing Irving.

The return of Holocaust denial − in America

Both films are occasions for celebration: the triumph of the historical record in court; vindication for a woman who spent her whole life reconstructing what was nearly obliterated. Yet, there are other, more sober observations to be made.

For one thing, despite having its made-for-Hollywood day in court, Holocaust denial is very much alive and well, and within a depressingly wide spectrum of political affiliations and demographies. It is embraced by conspiracy theorists, the fringes of the extreme left and right, even among ordinary people old enough to have lived through WWII as teenagers − and at the very pinnacle of American politics.

Donald Trump’s foreign policy adviser, Joseph Schmitz, has come under fire for downplaying the extent of the Final Solution: he is alleged to have opined that “the ovens were too small to kill 6 million Jews.” Anti-Trump journalists have been bombarded with both Holocaust denials and parodies, often grotesque. The Green Party VP candidate, Amaju Baraka, has a very public history of working with a well-known Holocaust denier, Kevin Barrett.

Unfortunately, it seems, Holocaust denial, and anti-Semitism more broadly, won’t be defeated either by the material evidence of the Oyneg Shabes archive, direct survivor testimony nor a one-time legal battle.

How women experienced the Holocaust

The work of history is not a monument erected once and admired ever after, but an infrastructure tended from the inside and out, over generations, a task inevitably shaped by those who take up the work. And while Deborah Lipstadt and Rokhl Oyerbakh stand as giants, they are also exceptions. For as long as historians have been studying the Holocaust, that work has been dominated and shaped by men.

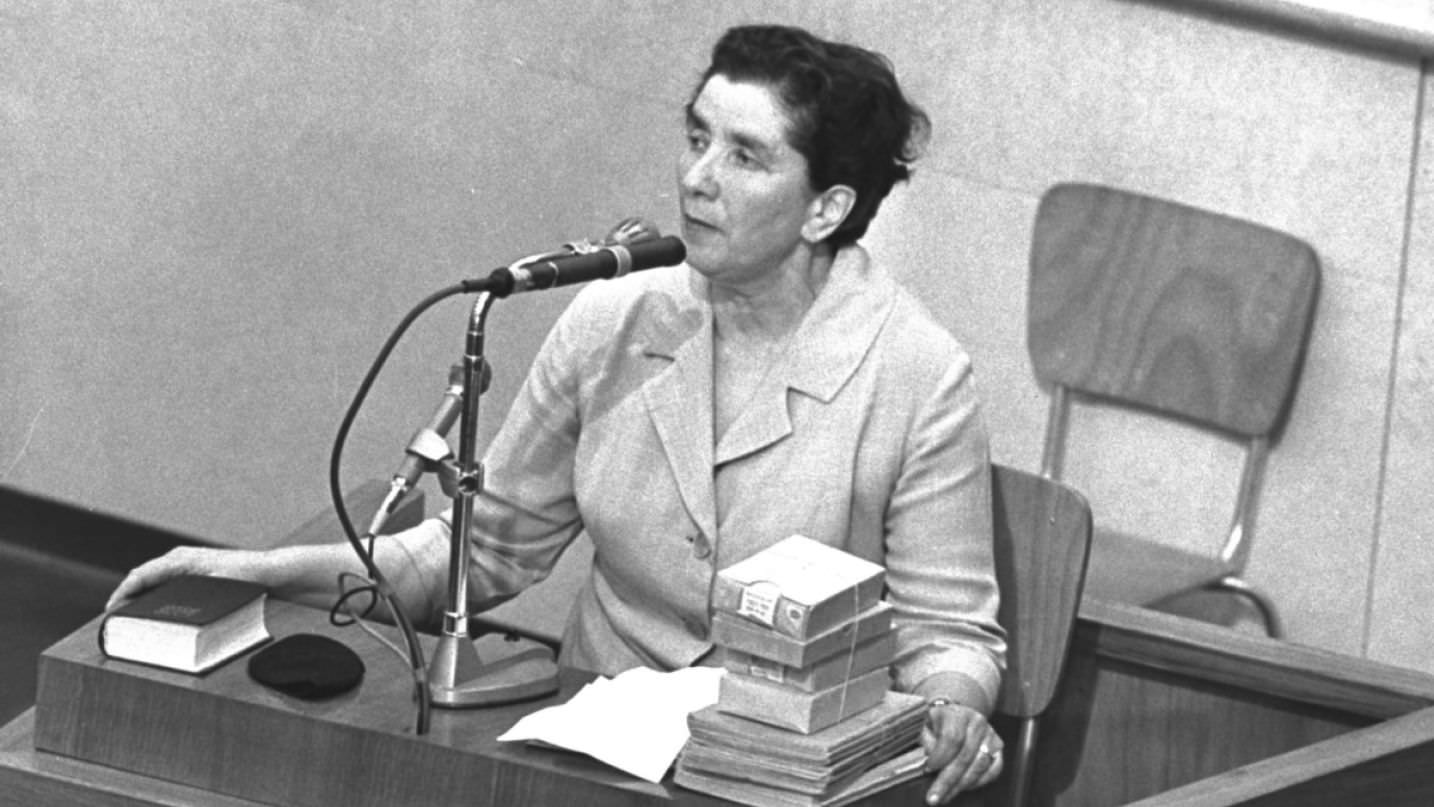

Rokhl Oyerbakh testifies at the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem, 1961. Credit: GPO

Consider: the first historical conference focusing on the experience of women in the Holocaust only came in 1983. The first book on the subject, “Different Voices: Women and the Holocaust” appeared in 1993.

Dr. Rochelle Saidel, the founder and director of the Remember the Women Institute, has spent decades studying the way gender shaped the Jewish wartime experience. She is also quite open about how her research has been met with skepticism by male academics. For example, she recalls being at a conference where she was heckled by a male historian when she mentioned rape as an aspect of sexualized violence during the war. And that was in 2006!

Indeed, rape and sexual abuse of concentration camp prisoners has been a taboo subject in the field. Yad Vashem didn’t index rape in survivor testimonies and the Steven Spielberg-funded Shoah Foundation interviewers were instructed not to ask survivors about such things. The lack of collected evidence creates a self-reinforcing impression that sexual abuse didn’t happen. It is only those with that rare force of will who are able to change the way we write our history.

German Nazi SS men on the Nowolipie street of Warsaw Ghetto during the uprising, 1943. Credit: National archives catalog

A full accounting of the female experience of the Holocaust is only just now beginning to be written. The third cache of Oyneg Shabes documents has never been found. 99% of Rokhl Oyerbakh’s enormous body of work has never been translated into English. There is still tremendous historiographical work to be done.

Historian Samuel Kassow notes that the “…Oyneg Shabes commitment to comprehensive documentation went hand-in hand with another important commitment: to post-war justice.” We must not lose sight of the ways that our understanding of history is incomplete − yet still subject to distortion and denial − and what is at stake in pursuing that work.

Originally Published HERE