“This is Not the Story of Someone Else”

This exclusive Yad Vashem interview with Miriam Ron was published in our newsletter Teaching the Legacy (December, 2008). Mrs. Ron discusses her experiences and memories surrounding Kristallnacht, the expulsion to Zbaszyn, and her childhood in Germany.

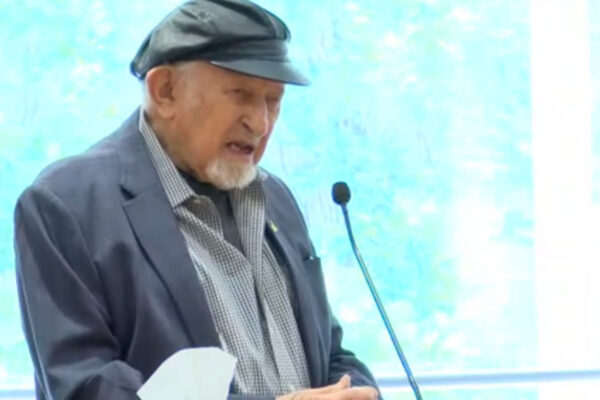

Miriam Ron, 2008

Could you please give us a short introduction of yourself?

My name is Miriam Ron. Before I was married my name was Miriam Shapira and we lived in Leipzig, Germany. I was born in 1924. My parents both came from Austro-Hungary, but my mother came to Germany in 1903 and my father in 1918.

“A nice neighborhood… we were on such good terms with the non-Jewish neighbors”

Can you describe your family life before Kristallnacht?

They were very accustomed to German culture, having come from German-speaking countries. We had a very nice family life and my father worked very hard to make a good living for us. We had everything – a nanny to take us out, we learned to play piano, and we went on wonderful holidays. We went a lot to Czechoslovakia, not for 10 days but for two months. My father only came to see us on weekends. We were a very tolerant but religious family. We went every Friday night and Shabbat [the Jewish Sabbath day] to the synagogue and my mother was very careful with kosher food. We were on very good terms with our non-Jewish neighbors. My father did really well in business and we were able to move to another neighborhood. All the streets were named after composers. We lived on Beethoven Street, which was a nice neighborhood. We had no Jewish neighbors, and we were on such good terms with the non-Jewish neighbors.

The conductor from the conservatorium lived with his wife on the second floor of our building. His wife and my mother were very friendly. Just to show you how friendly, my brother had a bar mitzvah. It was in February and it was snowing. First of all it was in the synagogue and afterwards, when we came home we prepared the room for the guests. It was snowing and my mother said, “People will be coming with dirty shoes, take out all the carpets,” and Mrs. Hof came and said, “What are you doing, you are having guests,” and she put down her own Persian carpets for us! She wanted it to look nice. We were on such good terms with them.

When did things change?

Everything changed one day. It was in 1935 and I was standing on the balcony of our apartment with my father and we heard people marching on the street. He said, “Come and see what’s going on.” He saw people marching and singing “When the blood of the Jews will be on our knives, we will be happy.” And one lifted his head and made a sign for us to see and my father had a real shock and he said, “It isn’t good that we live here amongst all these non-Jews, we have to move to another quarter.” We don’t know what’s going on.

“This is the country of Schiller, Goethe, Mozart – nothing will happen to us in such a cultured country”

What else changed?

Then of course we couldn’t employ a non-Jewish maid in our house and I was forbidden to go to the non-Jewish school so my brother and I were very pleased when our parents moved to a Jewish neighborhood and I was near the school. But every time we heard that people were leaving Germany my father said, “It’s so stupid – it’s terrible to be a refugee.”

My father remembered when he was a refugee living on the Austrian/Russian border after World War I. He said, “I was a refugee in Vienna and it was terrible and I don’t want to be a refugee anymore. – And what are you worried about? This is the country of Schiller, Goethe, Mozart – nothing will happen to us in such a cultured country.” This is what he said every day. When he saw people marching in the street he said, “We should tell the police.” He was so naïve, you couldn’t imagine.

Your parents were Ost Juden [East European Jews]. Was your family involved in the expulsion to Zbaszyn?

I am so surprised that nobody mentions this, which happened on the 28th of October, 1938, ten days before the pogrom [riot or massacre against Jews]. In our Jewish school the boys were praying in the morning. The girls didn’t have to, but they had to prepare breakfast for the boys to eat after praying. It was the turn of my friend and I to make the tea and we had to be at school at 7:00 instead of 8:00. I was already dressed and ready to leave the house when I heard knocking at our door. When I opened the door, two tall policemen were standing at the door. They asked, “Where are your parents?” I told them they were asleep. “Wake them up, you are going to Poland.” I answered, “What? What do I have to do with Poland? I was born in Germany.” He said, “Take me to the bedroom of your parents.” They both went into their bedroom and put on the light and said, “Get up. You are going to Poland.” My mother thought it was a bad dream. They said, “Don’t ask questions, you are going to Poland.”

“At 7:00 in the morning I was a student, and at 5:00, I was a criminal”

My father thought there was a problem with his income tax returns. My mother told me to wake up my 16-year-old brother. My parents asked why they were going to Poland – could they take something with them? The policemen said, “You are going to such a cultural land.” (When Germans talked about Poland they said “dirty Poles”). “No,” he said, “don’t take anything with you.” My father phoned his brother and asked him to take the keys to our apartment. He asked my father, “What have you done?” My father answered, “Nothing.” My aunt came and took the keys but when she got home, the police were in her house, and they really were sent immediately to Poland.

I will never forget my neighbor. She was a widow. She was wearing her nightgown, had hastily put on her overcoat and was carrying a little handbag. When I asked her why she wasn’t dressed, she told me the police didn’t give her time.

We were taken and crammed in to the gymnastics hall of the Jewish school. We saw all the people we knew from the neighborhood who were of Polish origin. My father had very high blood pressure and he couldn’t breathe. He called a doctor who said, “This man has to go hospital, he can’t be transported.” My brother said, “We will never see you again. We will be in Poland and you will be in Germany.” Every half hour a bus came to take the people to the railway station. My mother didn’t want to push, so we took the next bus and as we got in people were pushed in with us. We were all standing and that way we arrived at the Leipzig railway station. On the way, one woman became crazy. They took us to a siding where they take animals, horses and cows. There were soldiers with bayonets standing every ten meters to make sure we didn’t run away. So you see, at 7:00 in the morning I was a student, and at 5:00, I was a criminal. It was terrible.

How did you avoid getting on the train?

We waited for the next train and I heard a woman telling a policeman, “Don’t let me go to Poland. I have all the papers for America.” The commander of the action let her go home to get her papers. I persuaded my mother to talk to the commander to tell him that our father was in a hospital. The train had arrived, and I saw the lady in the nightgown pushed onto the train. My mother talked to him and he relented. When we told him we speak German with the Leipzig accent, he told the policeman to take us home. This was our first miracle. They thought we were German and not Polish.

Only five or six people were sent home, and we were three of them. We returned home. My father was still in the hospital. On Shabbat [Saturday] morning we had a telephone call. Though we were religious, we answered the telephone. It was the police station, asking for the Shapiro family. We had no papers. My mother told them they had the wrong number. So we had to run away quickly. We hid in the park, we moved from bench to bench, we were wet, hungry, and cold and eventually found shelter with a Professor Levy who was of German origin. My mother said we would go to see him and pretend it was a normal Shabbat visit, but he realized what had happened. He saw our faces, took us in, and gave us hot drinks. We stayed there the whole day. He also had a little boy with him who he had taken away from his parents at the railway station. He was an outstanding person.

When did you find out the reason for this aktion?

After Shabbat we listened to the radio and we learned what had happened. We didn’t know. After the Evian conference in July, 1938 the Poles decided that from November 1, Polish passports belonging to Ost Juden would be cancelled, but all those who still had a valid Polish passport were expelled from Germany immediately. Over three days these people were pushed between the Polish and German borders, in rain and mud, and the Germans took their possessions away. So we were really lucky.

“For years I thought I was dreaming and that it was not true”

Do you think what followed was pre-arranged?

What happened – I am sure the Germans had prepared this pogrom a long time ago but had no real reason to do it. After the German third secretary to Paris was shot and killed by Hershel Grynszpan, we heard that the German people had to react against the Jew who had murdered a German official and that was the reason for the pogrom, but we didn’t know this yet.

Leipzig, Germany, the Gottschedstrasse Synagogue during Kristallnacht

What do you remember about the 10th of November, 1938?

What happened on the 9th of November in the evening I don’t know, but in the morning I wanted to go back to school. Our class had 35 children, and after the Zbaszyn pogrom there were only 10 children left. My father told me not to go to school. We had 17 synagogues in Leipzig and my father wanted to go to pray in the morning, but everyone said, “Don’t go, don’t go – the synagogues are all burning – there are no synagogues anymore.” So we stayed home and waited to see what would happen. At 10:00 there was a knock at our door. It was the man who used to work for my father. “Run away as fast as you can. I saw 25 people coming to your house. They are now at the house next to you. Run away.” So again we left everything and ran away through the back entrance and we didn’t know where to go.

Sometimes I dream about what I saw. I saw a piano being thrown out of the window of an apartment next to us. For years I thought I was dreaming and that it was not true, but later I read about it. One of our non-Jewish neighbors shouted, “Run, run Jews, you can run to the Dead Sea and drown there.” So my father wanted to hire a taxi, but the driver said, “I am sorry I can’t take you, they will break the windows if they see there are Jews in my taxi.” My mother thought we should go to where there was a shopping center, where we would be inconspicuous and we could pretend to do our shopping there. Then my mother saw the shop where we often went to buy shoes and stockings and she said the man is so friendly to me [that] we will go into his shop. When the store owner saw us he said, “Oh I am sorry. They will break my windows if they see that Jews are here. Sorry – you have to go.” So again we were in the street.

Did anyone help you?

Another taxi came and my father said, “Do me a favor, take us somewhere.” He said, “Come in – come in, I am so happy to do something against these damned Nazis.” When my father asked why he was helping us, he said all his family was in a concentration camp because they were Communists. “I am so pleased to help you.” He told us he had passed by the Polish consulate and seen a large crowd of Jews hiding there, even in the garden. They had Polish passports so they had diplomatic immunity and were theoretically on Polish soil. The Germans couldn’t enter. When we arrived there, we had to park on the other side of the street near the Supreme Court, which was connected to the university. The students came up onto the roof of the Supreme Court with buckets of garbage and when they saw Jews, they tipped the garbage on our heads. We entered the consulate and as there was no room inside we waited in the garden. We saw wounded children who had been beaten up. After a few hours we heard someone calling, “Frau Shapiro” – it was the man who worked for my father, who had brought us sandwiches. He told us that everything in our house had been burned and broken. My mother said, “Really?” We thought she didn’t understand but she said, “I do understand, but I am looking at my children who have no bleeding heads and arms. It doesn’t matter.” [i.e., she was relieved that we were not physically hurt].

At about 5 o’clock in the evening the Consul himself said through a loudspeaker, “Everyone who has a Polish passport should go home, as they are under our protection.” Can you imagine that 10 days before, it was a disaster to be Polish and now it was good to be Polish! He knew that there were also German Jews sheltering, so he was very nice and said, “Only Jews with Polish passports should go home.”

When we got home, we saw there was no door to the apartment, not one book left. We were tired and wanted to go to sleep but how can you go to sleep with an open door. All our books were burned. We saw burned pages on our way home. They just made a fire outside our house and burned everything they could. My mother found our income tax book on the kitchen table. This they left and she put it in the oven and said she wanted to finish it.

But how can you go to sleep without a front door? We put a table where the door had been and buckets on the table so if someone pushed the door it would make a noise. Then in the middle of the night, the bucket fell down and I started crying. I hadn’t cried all day, but it was too much. It was only a neighbor and she wanted to tell us the aktion was over. The German nation has calmed down after what has happened. They made out it was the ordinary Germans who had taken part in the pogrom and not the Nazis. So that was the end.

“I will tell you that you must be more careful than all other people not to be antisemitic”

What was the aftermath of Kristallnacht?

Shortly afterwards, two elderly German Jewish neighbors committed suicide. They weren’t religious. In fact, they hardly knew they were Jewish. My piano teacher came to tell us that all the German Jewish men including her husband were sent to concentration camps. After a few weeks she received a parcel and she had to pay to receive it. You know what was inside the parcel? Her husband’s ashes. Then of course it was impossible to stay in Germany anymore.

On the 11th of November my mother saw one synagogue still burning. She went to the police station. She asked why everything was still burning and why everything was so destroyed. She even went to the police station to complain and they answered her that if she didn’t know who had done it, they also didn’t know. My mother was so naïve. Before October we were patriots. If they arrested Jews, we thought it was because they were criminals not because they were Jews.

This is not the story of someone else, it’s the story of me. It’s with me all the time. It’s there.

Did you have any friends left in the neighborhood after Kristallnacht?

We had one neighbor who wrote us a letter – I don’t know how he found us – and he wanted us to write a letter in 1954 to say he wasn’t a Nazi and that he was very friendly with us.

You never wanted to go back to Germany?

No, but in 1988 my husband was invited to Karlsruhe and I went with him. I was allowed to go to Leipzig, East Germany, but while we were in Karlsruhe they asked if I would speak to some students on November 10th about Kristallnacht; there I spoke to a class of girls aged 14, which was the same age I was during Kristallnacht. I told them everything I have told you in German. One girl asked if she should feel guilty and I said you know what, you are 14. How can I say that you or your parents are guilty. But I will tell you that you must be more careful than all other people not to be antisemitic, not to hate people because of their nose, because of their hair, and you know what, think about it – everybody is allowed to eat chocolate but not somebody whose grandmother died from diabetes. If your grandmother died from diabetes, you aren’t allowed to eat chocolate. This is also the message I would tell students today.

Originally published at YadVashem.org