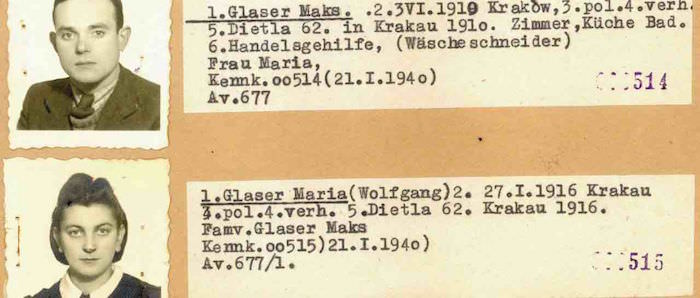

The permit allowing Yuval Yareach’s grandmother and grandfather to stay in Krawkow during the Nazi occupation. Yuval Yareach

Haaretz – In recounting the harrowing experiences of his grandmother during the Holocaust for an ambitious new book project, Israeli author Yuval Yareach faced a daunting challenge: He had hardly ever spoken to her about it.

By the time he set out on his mission to turn Manja Wolfgang’s life story into a work of literature, Yareach was already in his mid-thirties, and his grandmother was long dead. But even had she been alive, as the title of his work suggests, it is doubtful she would have cooperated.

In his introduction to “Hashtikot” (“The Silences”), Yareach – a high school English and computer science teacher from the Negev community of Lehavim – laments that his grandmother rarely spoke and always avoided questions about “that subject.” In his childhood memories, he recounts, she often appears sitting on a chair in the kitchen, staring silently into space. That silence, he understood even as a young boy, spoke volumes.

“The Silences,” Yareach’s debut literary work, is not quite fact yet not quite fiction. Based on many of the real-life experiences of his grandmother, it also relies heavily on his own imagination. He therefore prefers to describe it as literature rather than historical research.

A photograph of Yuval Yareach’s grandmother, Manja Wolfgang. Eliyahu Hershkovitz

The bare bones of his grandmother’s story, which served as his outline, had long been familiar to him: That she was born and came of age in the once very Jewish city of Krakow. That she married his biological grandfather Max Glaser when she was in her early twenties and gave birth to their daughter Sara (“Lala”) soon after the Nazis invaded Poland. That they decided to give the baby away to Gentile acquaintances when conditions in the Krakow ghetto, where they had been forced to move, turned unbearable. That they were taken together to the Plaszow concentration camp (where Oskar Schindler famously saved Jews by giving them work in his factory) during the liquidation of the ghetto. That from Plaszow, his grandmother was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. And that against all odds, she somehow survived the death camp, eventually making her way to Israel.

What he didn’t know were all the details in between. It was this quest to fill in the holes in the story that sent him on a 10-year-long journey back into the past. It involved several trips to Poland, where he met with descendants of the family who hid his mother, visited Krakow and Auschwitz and pored over thousands of documents and newspaper clippings in local libraries and archives. Back home in Israel, he immersed himself in documents and testimonies provided by Yad Vashem and interviewed close to 20 survivors who had passed through many of the same sites of infamy as his grandmother, hoping to get a better sense of her experiences through theirs. He also read every book he could get his hands on that promised some new tidbit of information. The shelves overflowing with Holocaust books in the otherwise sparsely furnished home he shares with his wife and 3-year-old daughter attest to his “psychopathic” desire, as he describes it, to get to the truth.

“It became an obsession,” said Yareach during a recent interview at his home. “I constantly feared that if I got something factually wrong, it could be used against me by Holocaust deniers.”

Which explains why before describing what took place on a particular day in his narrative, he would first search old newspaper clippings to find out what the exact temperature had been. Every detail that could be checked he corroborated, and where no information existed, he put his imagination to work. Otherwise, how could he have described intimate moments during Max and Manja’s honeymoon or the challenges his grandmother faced while menstruating in a concentration camp?

Yareach, 45, sees himself as a member of the “second-and-a-half generation” – children of child survivors, with parents who remembered very little and with grandparents who spoke very little about what they remembered. It follows that much of his information about the Holocaust while growing up came from books.

Reading so many books about this period, he says, allowed him to understand what was missing in the genre and where he could make his mark. “There were hardly any that provided detailed descriptions of daily life,” he says. “I decided that would be my goal. That, and providing detailed descriptions of Jewish life before the war.”

A photograph of Yuval Yareach’s biological grandfather, Max Glaser. Eliyahu Hershkovitz

Yuval Yareach’s grandmother Manja Wolfgang and her second husband, Moshe (“Monik”), after the war. Eliyahu Hershkovitz

His 560-page book (currently available only in Hebrew), which begins on the day his grandmother is born and ends with her death, is part of a relatively new genre: literary and cinematographic works produced by children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors determined to fill in the blanks in their family stories and to break the silence about what happened.

Yareach always knew he wanted to write, but felt at a loss for a good topic. About 10 years ago, while in between jobs, travels and apartments, he found himself living temporarily in his old room in his parents’ home, and it was there that he experienced his eureka moment. “I suddenly stumbled upon an old cache of letters, written by my mother when she was a young girl, and I realized that here was the story, it was the story of my family, and it had been sitting right there in my lap all this time.”

His initial attempts to find a publisher failed. Frustrated, Yareach decided to seek advice from a beloved Israeli author who had written his own highly acclaimed Holocaust novel, also very much influenced by a true personal story. That author was the late Amir Gutfreund, whose “Our Holocaust” has been translated into half a dozen languages. Yareach did not know Gutfreund personally but heard that he would be delivering a talk at a nearby campus and decided to show up with a copy of his manuscript. Gutfreund graciously agreed to take a look at it, and within a matter of weeks, Yareach received a call from Zmora Bitan, a leading Israeli publishing house (which also released “Our Holocaust” and had previously rejected “The Silences”) asking him when he was available to sign a contract.

Today, Yareach is working on his second novel, this one about the life of a Jewish family in Algeria. Out of his comfort zone? Not really, he says. His wife, he points out, is a descendant of Algerian Jews.

Originally published HERE