Clothes are important to Olga Horak. A self-taught seamstress, she was in the rag trade all her working life, running a factory and a fashion boutique in Sydney.

Even now, at 89, she designs and makes her own dresses — “I’m very fussy,” she explains, “and all the beautiful clothes in shops are for young people.” That rough blanket in her hands is important to her too. She acquired it on April 15, 1945, in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, when she was 29kg of skin and bone, with no underwear or shoes, dressed in rags. A fleeing guard dropped the blanket on the day the camp was liberated. Olga wrapped herself in it. For a long time it was all she had in the world. You’ll shudder when you hear what it’s made of.

Olga didn’t talk publicly about the Holocaust until 1991, when her two daughters were grown up and she’d retired. Now, as a volunteer guide at the Sydney Jewish Museum, it’s her life’s work to tell her story. How her family were taken from Czechoslovakia to Auschwitz, where she came face to face with Dr Mengele. How she endured nine months of starvation and slavery there and at Bergen-Belsen. How she made it out alive. How her mum, dad, sister and grandma didn’t.

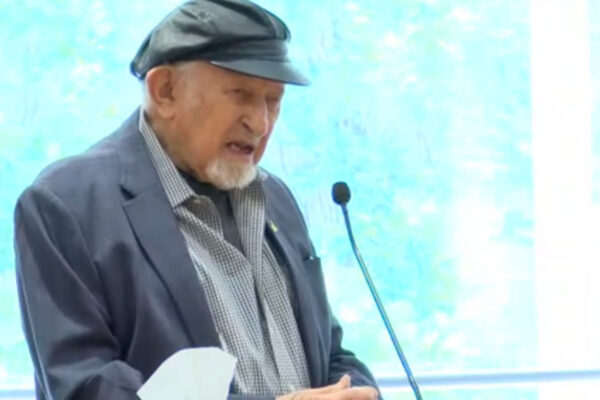

Olga, pictured in a shot from the National Photographic Portrait Prize, to be unveiled on March 18, says it’s “not at all therapeutic” to talk about it — her hands fret at a balled-up tissue as she does so — but it’s nice to be listened to, to feel appreciated. She lost her husband recently; the museum is “my second family”, she says.

Now a great-grandmother, she has lived under the bright Aussie sun since 1949, but the war casts long shadows. “People say, ‘Live for the future, don’t live in the past’. But I don’t live in the past … the past lives in me.” That blanket is a visceral, awful reminder: it’s made with human hair, cut from the heads of camp inmates.

Originally published HERE.