Hundreds of people marched through the port city of Thessaloniki on Sunday, marking 80 years since the deportation of Greek Jews during the Holocaust.

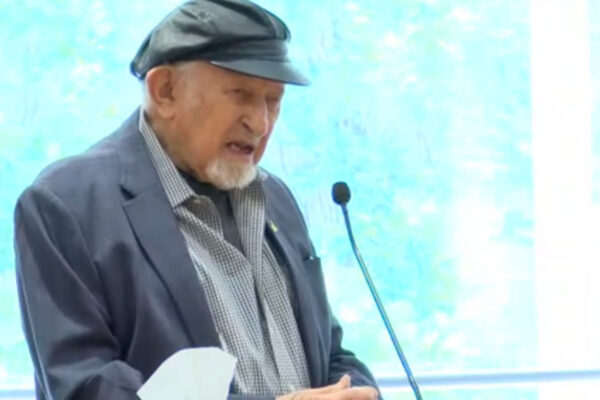

From left to right: Thessaloniki Holocaust survivor Esther Yaron, Vice President European Commission Margaritis Schinas, President of Greece Katerina Sakellaropoulou, Minister Ofir Akunis, President of the Greek Jewish Communities David Saltiel, Israeli Ambassador to Greece, Noam Katz & Director of the European March of the Living, Michel Gourary

The commemoration comes at a time of burgeoning relations between Israel and Greece, and amid increasing awareness of what happened to the latter country’s once vibrant Jewish population when it came under German occupation during World War II.

Sunday’s event, organized by the European March of the Living together with local city and state government officials, was attended by Greek President Katerina Sakellaropoulou, senior Greek and Israeli officials, and Holocaust survivors and their families. It followed the path that the Germans forced the city’s Jewish population to take back in 1943, from a central square opposite the port to the old train station, from where they were deported in cattle cars to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The Germans made the Jewish community pay for “train tickets” to Auschwitz.

“We are here not only to remember the Jews but for all of us to say ‘Never Again,’ ” Sakellaropoulou told JNS. “I come every year, and as long as I am president, I will be here.”

In her address in Greek at the abandoned train station, she said that the city of Thessaloniki—once known as the Jerusalem of the Balkans for its thriving Jewish community—had, over the last two years, accepted its share of responsibility for the tragedy that took place when the Germans occupied their city.

Before World War II, about 80,000 Jews lived in Greece in 31 communities, two-thirds of whom lived in Thessaloniki. Only 10,000 survived the Holocaust. Today, about 5,000 Jews live in Greece.

“We are here to remember the unforgivable actions of the Nazis’ pure evil and to remember the wonderful legacy of Thessaloniki’s Jewish community,” said Minister for Innovation, Science and Technology Ofir Akunis, speaking on behalf of the State of Israel.

He noted that part of his family originated in Thessaloniki but had managed to escape.

“For me, personally marching here today with all of you as a minister of the Israeli government is a great triumph. It is a victory of the spirit…of the families, of the communities and of the entire nation,” he said. “The democratic State of Israel is the proof of our victory.”

The US ambassador to Greece said that whenever a Jewish cemetery is vandalized it is a “modern incarnation of Kristallnacht,” the 1938 Nazi pogrom throughout Germany that served as a precursor to the Shoah.

“We cannot allow the horrors of the Holocaust to be trivialized or forgotten,” said Ambassador George J. Tsunis. “We will not let the losers of World War II rewrite history.”

A roundup of 9,000 Jews in Salonica, July 11, 1942. Source: Bundesarchiv via Wikimedia Commons.

Honoring the legacy

Under a crystalline blue sky on a sun-drenched spring day, the marchers, young and old, carrying white balloons reading “Never Again” in Greek, took the nearly 1-mile-long path where the Jews of the city were forced to march on March 15, 1943, in the first of 18 “transports” that continued through August.

“I feel I am walking back in time to the stories of my family who are no longer with us,” recounted survivor Esther Yaron, 80, from the central Israeli town of Pardes Hanna.

Yaron was six months old when she and her mother were rescued from the last transport from the ghetto in the Baron Hirsch neighborhood to Auschwitz by Greek partisans and her father. “My story is the story of the nation’s rebirth,” she said.

“For three days I haven’t been able to sleep thinking how I will stand here in this place where my relatives were taken to be killed,” said Mazal Kapetis, 78, from Tel Aviv.

Her parents were from Thessaloniki but went to work in a port in pre-state Israel in 1933 and so were saved. “I look around here and cannot believe that we are now 80 years later,” she said.

“Every time I come here I remember the stories of my father who was on the first transport to Auschwitz and the sole survivor,” said Yehuda Gerse, 67, from Haifa. He said his grandfather read the Book of Esther on the train to the death camp.

“We are here to honor the legacy of our parents,” said Tzvi Shlomo, 75, from Rehovot, whose mother and father survived deportation from Thessaloniki. “Everybody else died.”

He has their camp entry numbers tattoo numbers etched on his person, one on each arm.

In the wake of the expulsion of Jews from Spain following the Alhambra Decree of 1492, Thessaloniki received a huge influx of Iberian Jews, making it one of the largest and most diverse communities at the time.

Due to the preponderance of Jewish port workers, the city’s harbor was closed on Saturdays and Jewish holidays, while Ladino—the Judeo-Spanish dialect of the Jews—was spoken throughout the city. Rabbinic luminaries such as Rabbi Shlomo Alkabetz (c. 1500-1576), composer of the “Lecha Dodi” hymn sung at the start of the Sabbath, and Rabbi Joseph Karo (1488-1575), author of the code of Jewish law known as the Shulchan Aruch, lived in Thessaloniki before moving to Israel.

A Jewish family of Salonika (Thessaloniki) in 1917. Credit: Archives Elias Petropoulos via Wikimedia Commons.

Rebirth

Officials said that it was only fitting that the city’s vibrant Jewish past should see a rebirth.

“My hope is that Thessaloniki will again become a center of vibrant Jewish life where people will feel safe and proud and that what happened to their grandparents will never happen again,” Margaritis Schinas, a city native who is the European Commission “vice president for promoting our European way of life,” told JNS. His responsibilities include combating antisemitism.

The ever-warming relations between Athens and Jerusalem have unquestionably contributed to greater Greek awareness of past events and efforts in countering antisemitism, officials said.

“There is no doubt that the friendship with Israel plays a big role and that there is a benefit,” said David Saltiel, president of the Central Board of Jewish Communities in Greece. “What happened [in the Holocaust] happened because there was no Israel.”

He added that construction of the Holocaust Museum of Greece is set to get underway this year in Thessaloniki.

The march was a sign of the changing times in Greece, where low-level classic antisemitism, especially in conservative elements of the Greek Orthodox Church, endures.

“The march would never have happened in Greece even 10 years ago,” said Leon Saltiel, a researcher and expert on Thessaloniki Jews. “It is a completely different setting and perspective.”

“The relationship between Israel and Greece is one of the main reasons we feel the change in the society,” said Benjamin Albalas, the chair of the European March of the Living and a Holocaust survivor from Athens.

The March of the Living, which organized Sunday’s event, is best known for its annual march from Auschwitz to Birkenau, which has been attended by 300,000 people since its inception three-and-a-half decades ago. In recent years, it has branched out to include marches in multiple European cities that once had large Jewish populations.

“The idea was to reach out to and educate non-Jewish youth who might not have gone to visit Auschwitz,” said Michel Gourary, director of the European March of the Living.

“The March of the Living is in essence the March of the Living of the Jewish people,” said Rabbi Yoel Kaplan, who heads the Chabad House in Thessaloniki. “It is a declarative act looking into the eyes of the world and saying that the Jewish people lives on.”