Every family has secrets, but some cry out to be revealed to the world.

That’s what San Francisco cinematographer Eli Adler learned when — well into middle age — he began exploring his father’s Holocaust past.

As a child growing up in Skokie, Adler knew little about what his father had suffered and lost in Poland, where an estimated 3 million Jews had been massacred. As an adult, Adler worked on uncounted films but never had made one of his own.

These two needs — to finally grasp his family’s tragic past and to put it on screen for all to see — converged in “Surviving Skokie,” a bittersweet, profoundly autobiographical documentary having its Midwest premiere March 13-15 at the Chicago Jewish Film Festival (I’m one of several people interviewed in the film).

The pain, anxiety and release that Adler felt in creating “Surviving Skokie,” which took six years, may be familiar to anyone bringing searing family narratives to the screen. For the burden of unearthing the dark truth is counterbalanced by the privilege of telling it. I learned that equation in making the PBS documentary “Prisoner of Her Past,” which, like Adler’s tale, involved tracing my parents’ Holocaust narrative, following it forward to Skokie and unveiling it for all to know.

The process can prove unnerving, particularly when you consider how deeply buried the past may be.

“Our family life seemed normal: birthday parties, barbecues and bicycle rides down Dempster Street,” Adler says in “Surviving Skokie.” “But when I visited my neighborhood buddies, I could tell there were things about my dad that were different than theirs.

“I would ask my dad: Why don’t I have any grandparents? Why don’t I have any aunts or uncles? Why don’t I have any cousins?”

Answers were not forthcoming. Like many Holocaust survivors, Jack Adler — Eli’s father — chose not to expound on horrific experiences for which words would prove inadequate.

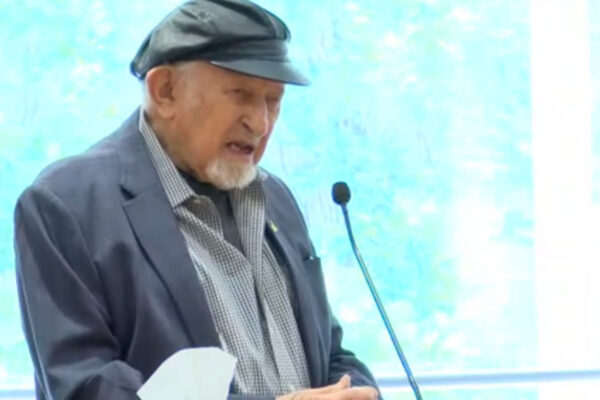

“No,” says Jack Adler, 87, “I did not talk at all” to his kids about what happened. “I did not want them to feel sad about what transpired.”

But the silence and the void increasingly weighed on Eli Adler, as it does on many children of Holocaust survivors as they age.

“The older I got, the more I realized there were secrets in our family,” he says in the film. “And discovering those secrets became almost like an obsession to me.”

He didn’t start to pursue his compulsion, however, until he was 55 years old, and it snuck up on him. In 2009, a friend had sent him an article about the dedication of the Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center in Skokie, and “that kind of piqued my interest,” he says.

So Eli Adler began delving into a difficult topic that had been lingering in the back of his mind for as long as he could remember. The more he learned, the more he wanted to know.

Armed with only a camera and a credit card, he began traveling to Skokie to conduct interviews. But his idea was to tell his father’s story, not his own.

Once another filmmaker joined the project, in 2011, the venture became decidedly more personal.

“I said, ‘It has to be about more than your dad,’ ” recalls Blair Gershkow, Adler’s co-director and co-producer on “Surviving Skokie.” “At some point I said, ‘Eli, you’ve got to be in this thing. We’re missing you in the middle.’ He was reluctant because he’s a cameraman. He’s behind the camera, not in front.

“I said to Eli: ‘I’m going to force you to be open, to be forthright, to expose yourself emotionally about this experience.’ ”

Ah, yes, there’s the rub — saying out loud what you’ve been afraid to even think about for most of your life.

For me, that meant traveling to my mother’s hometown, Dubno (formerly in Poland, now in Ukraine), to try to find the story she never told me. To try to understand why, at age 69, she had begun reliving her unspoken Holocaust past, believing that everyone was trying to kill her (as they indeed had been during her childhood, as I ultimately learned).

For Eli Adler, the quest meant not only answering Gershkow’s questions on camera but, more painful, traveling with his father to the scene of the crimes: the Polish shtetl of Pabianice, where Jack Adler spent the first beautiful 10 years of his life, before the Nazis arrived in September of 1939. By February of the following year the town’s Jews were herded into a cramped ghetto.

“It was hard for a youngster like myself to comprehend why just because I am Jewish they’re moving us to a certain section of the city,” Jack Adler says in the film. “Why are they doing that? … There was little food to eat. No medical care. And as a result disease ran rampant throughout the ghetto.”

The severe conditions killed Jack Adler’s mother and brother, and his grandmother was sent to her death in the Chelmno killing center. In 1942, surviving Adler family members were shipped to the still more crowded ghetto in Lodz, where they would suffer 26 months of deprivation and humiliation.

In the film, we watch as Jack Adler tell stories that Eli Adler never had heard: How Jack Adler had been rounded up to be executed at Chelmno but was spared when that day’s quota was filled; how Jack Adler had saved his sister from death, though only temporarily.

Jack Adler weeps on camera as he reveals these stories, pain and suffering playing on his son’s face.

Then the two step into a cattle car of the kind that took Jack Adler’s family to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp in 1944, where he spent 10 days before being sent to a subcamp of Dachau.

“It was an emotional journey, where I felt it all,” remembers Eli Adler. “I felt anger. … I felt sadness. And the box car in particular — to be with my father, who had been with his father in a box car that could have been the identical car. Who knows? It just brought it all home for me.”

In making a film like this, there often comes a moment that crystallizes the terror of the story more succinctly than any other. For me, it was standing in the fields where my mother’s family and 12,000 other Jews were machine-gunned to death. As I tried to comprehend the enormity of those events, the last surviving eyewitness to one of the massacres described to me — through tears — what she saw there as a child.

For Eli Adler, the most bitter revelations occurred as he was documenting his father’s late-in-life return to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where Jack Adler had been invited to speak to students in 2012 about what happened there.

In the film, Jack Adler recalls what Auschwitz inmates told him as he stepped off the cattle car: “When you march, look strong, if you want to live. Straighten up and march. Because you’ve just arrived to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.”

Here is the bleakest moment of the film and of Jack Adler’s story, the moment his 11-year-old sister, Peska, was selected to be among those executed at Auschwitz.

“That’s when my little sister was separated again from us,” says Jack Adler. “I’ll never forget her face. As she turned around her eyes were speaking: ‘Don’t leave me alone, don’t leave me alone.’ ”

Why do we travel so far to hear such stories? Why do we ask witnesses to relive such horrors and share them with us, so many decades later?

The answers vary but some common yearnings are unmistakable.

“I spent all of my life up to that point just wondering,” says Eli Adler, 61.

Now, “I feel a little more complete as an individual, having had that experience with my father. … It was an emotional roller coaster. Interviewing my father — we interviewed him four times for the film, and it was like peeling back an onion. Each interview revealed a little more of his past.

“And the last interview we did with him, when he tells the story about how he was selected with a bunch of other boys to go to Chelmno and was sent back home because the quota was filled — I never heard that story, and it broke me down.

“It was difficult for me to see him relive some of this stuff, but I knew that we needed to do it. And it was for the greater good.”

That seems inarguable, for the survivors who were children back then — such as Adler’s father and my mother — are the last among us to have lived this story. The next generation carries it forward, on film, in books and anywhere else narratives can be revisited.

“I almost feel obliged to carry the torch for those who no longer can carry the torch,” says Eli Adler, whose film also addresses the threatened neo-Nazi march in Skokie in the late-1970s.

“I want future generations to know. … I think it’s very important,” says Jack Adler. Since those terrible years, “humanity, unfortunately, did not learn much,” he adds.

Though Jack Adler never discussed his past in detail with Eli Adler before the making of “Surviving Skokie,” in 1992 he began telling his story to school groups and others. He recounts how he was liberated by the United States Army in May of 1945, coming to New York in 1946 and to Chicago the next year. Revisiting these events still is not easy, he says.

“Each time I do it, it’s hard,” says Jack Adler, who now lives in Colorado. “But I figure the importance outweighs the hardship I encounter. … I can speak not only for myself, but for those whose voices were silenced forever.”

Now, through “Surviving Skokie,” he can speak to thousands, for all time.

If Jack Adler had it do over, would he once again go through the angst of making such a film?

“Without hesitation,” says Adler.

Me too.

“Surviving Skokie” plays at 4 p.m. March 13 at the Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center, 9603 Woods Drive, Skokie; 7 p.m. March 14 at Landmark Century, 2828 N. Clark St.; and 7 p.m. March 15 at Landmark Renaissance, 1850 2nd St., Highland Park. Visit www.jccfilmfest.org orwww.survivingskokiemovie.org.

“Prisoner of Her Past” will be rebroadcast on WTTW-Ch. 11 during Holocaust Remembrance Week in May. Visit www.wttw.com orwww.prisonerofherpast.com.

Originally published HERE.