This week I mourn the death of Elie Wiesel, who was a role model of mine. Wiesel’s story is also my story. We were born within a few months of each other in 1928, we grew up in towns about 60 miles apart, and in the spring of 1944 we were both deported to Auschwitz. Upon arrival we both saw our families be torn apart as men were separated from women. And we both lost our fathers: mine was sent to the gas chambers immediately, while Wiesel watched his father die months later, a victim of the brutal regime of slave labor.

Wiesel and I were both liberated in 1945, and started new lives in new countries. But starting in the mid 1950s, an important difference between us emerged. Wiesel began to write about his experiences, and published his most famous work, Night. I remained silent. At that time most people didn’t want to hear about the camps, and most survivors didn’t want to talk about it. Even when that mood changed somewhat in the 1960s and 1970s, I was quiet about what had happened to me. I told my children and answered their questions, but I preferred that my clients, colleagues and friends didn’t know about my past. I didn’t want their pity, and I didn’t want them to see me as a victim.

Wiesel became the voice of survivors like me. I admired him for his brilliance, for his writing and for the eloquence with which he spoke about his history—for it was my history as well. The details differed, but the suffering, humiliation, and loss were a collective experience: his, mine, and that of many others.

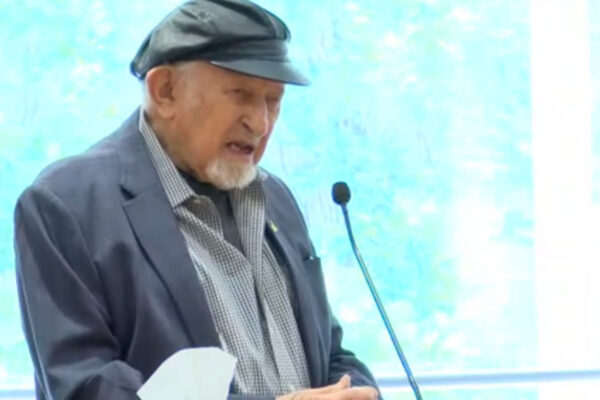

For years I continued living in silence about my past, but as I grew older I became more aware that once the survivors were all gone, there would be no one to bear witness to what had happened. Eventually I decided that, like Wiesel, I needed to be public about being a survivor and that, in my own small way, I should contribute to the mission of educating the world about the Holocaust. And so for more than three decades I have been telling my story to groups all over the United States—mostly to high school kids, but also in community centers, churches, synagogues, and universities. Recently, I was able to share my story with over two million people through a BuzzFeed video about my liberation from the camps. The letters and comments I receive make it clear that there is no education about the Holocaust that touches people more strongly than hearing from a survivor of the camps.

I am 88 years old and fortunate to still be in good shape. I will keep speaking to audiences until I can no longer make it onto a stage. But there are not many years left for those of us in the dwindling, final group of survivors. For the time my mind and body will give me, I will carry on the work started by Elie. I will tell our story, and I will speak—especially in these times—about the tolerance and compassion necessary to prevent what happened to us from happening to others. And when it is hard to speak, as it sometimes is, I will remember my favorite words of his.

“Nobody is stronger, nobody is weaker than someone who came back. There is nothing you can do to such a person, because whatever you could do is less than what has already been done to him. We have already paid the price.”

From Gene Klein’s daughter, Jill Klein

In 1981, a friend of mine gave Elie Wiesel a copy of a college paper I had written about my father’s Holocaust experiences. He wrote me a letter that stayed on my office wall for years. In it he said: “…I cannot tell you enough how important it is for you and your peers to write more and more and more.”

I did write, and three years ago I published my book, We Got the Water: Tracing My Family’s Path Through Auschwitz. I wrote this book in the interstices of a life in which I also built my academic career and raised my daughter. Early on Saturday mornings, between classes I was teaching, and while ignoring my email inbox, I interviewed my father and his sisters, added new paragraphs and rewrote old drafts.

And so, Professor Wiesel, thank you for your inspiration and encouragement. I did indeed write more, and more, and more. My book is the greatest gift I was able give to my father and my aunts. It is also the most powerful tribute I could give to my grandfather, who was killed in the gas chamber at Auschwitz. Aside from my daughter, it will be my greatest legacy. And, in a way, it is your legacy as well.

Originally published HERE